Αrt2658 Παρασκευή 17 Φεβρουαρίου 2017

China's Hedge Fund Elite Live in Their Own Private Village

Hedge funds didn't exist in the world's second-largest economy five years ago. Now they have their own private village.

The Yuhuang Shannan Fund Town in Hangzhou, China.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Bloomberg News

Nestled between the Qiantang River and Jade Emperor Hill, the village of Yuhuang Shannan feels a world removed from the surrounding metropolis of Hangzhou. The city of 9 million is hectic and loud, while this gated community—on the same site where emperors in the Song dynasty prayed for good harvests centuries ago—is quiet and green, exuding the feeling of a laid-back, high-end oasis.

Like Greenwich, Conn., the leafy town an hour’s drive north of Wall Street, Yuhuang Shannan, about an hour from Shanghai by high-speed train, has become a big hit with the hedge fund crowd. So big, in fact, that local authorities turned the entire village—until recently a hub for the design industry—into an exclusive enclave for China’s aspiring masters of the universe.

These days, resident money managers and their guests are the only ones allowed past the guarded entrance to Yuhuang Shannan. Inside, villa-style office buildings offer rows of trading terminals and waterfront views. There’s a private elementary school partly staffed by non-Chinese teachers, a modern medical center, and a club for after-work schmoozing—all designed with discerning financiers in mind. Even local government officials are eager to please, standing ready to help the funds raise cash from state-run investors and navigate the bureaucracy.

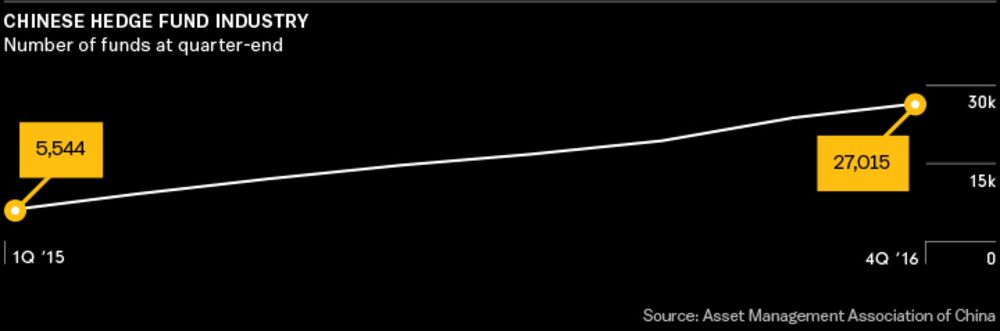

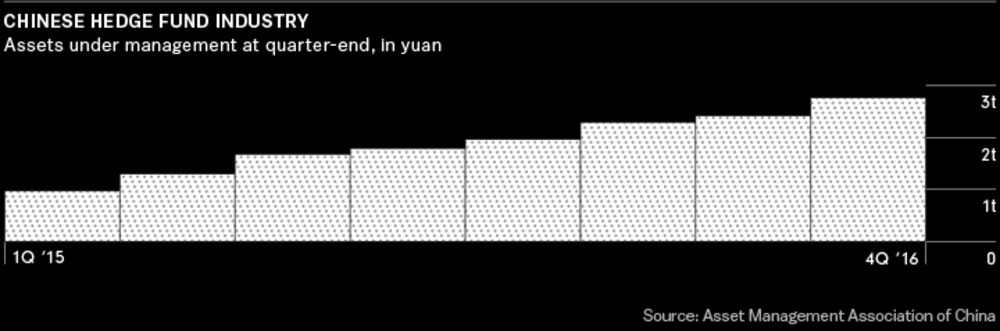

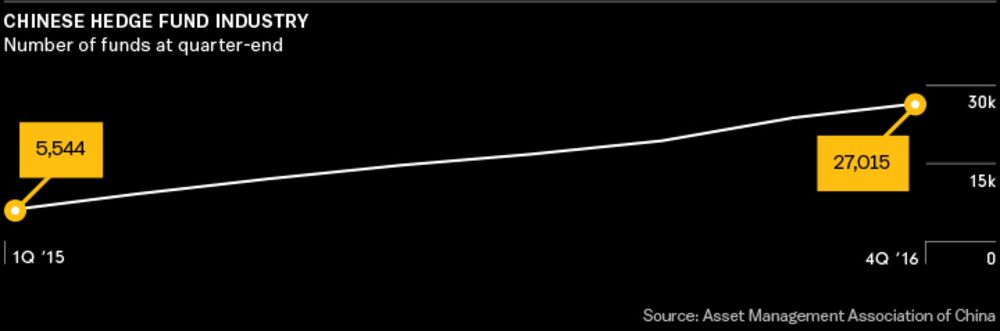

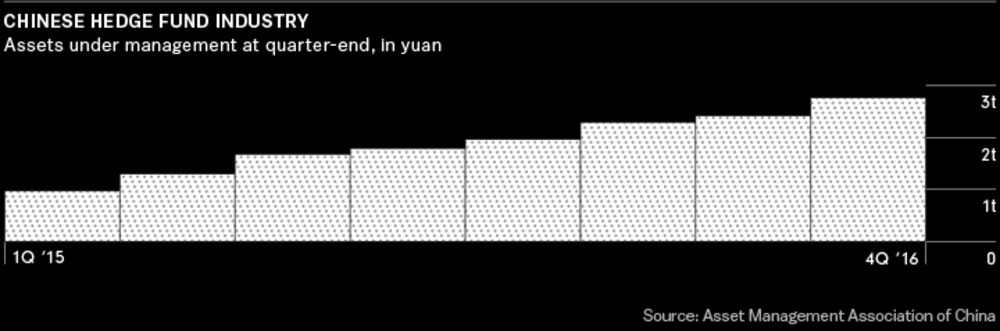

In China, the total number of hedge funds almost doubled in 2016, and assets under management have more than tripled over the past two years

It’s no wonder more than 1,000 hedge funds and private equity funds, overseeing a combined 580 billion yuan ($84 billion), have registered in the village since its official rebranding in May 2015 as, straightforwardly enough, Yuhuang Shannan Fund Town. With subsidies amounting to 30 percent of a typical firm’s tax bill adding to the area’s appeal, Yuhuang Shannan now boasts one of China’s largest hedge fund clusters outside the megacities of Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen.

Alumni of Goldman Sachs and Bank of America Merrill Lynch have moved in, while a representative of Connecticut-based Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund firm, is said to have made a recent visit. “The natural environment is fantastic, and I believe the cluster effect will become stronger and stronger,” says Ted Wang, a former co-head of equities trading for the Americas at Goldman Sachs who now runs Puissance Capital Management, a global investment firm with offices in New York and China. Wang has registered two of his Chinese equity funds in Yuhuang Shannan.

Not too long ago, the thought of a hedge fund village in Hangzhou, or anywhere else in China, would have struck most observers as absurd. Hedge funds weren’t officially recognized by Chinese lawmakers until 2012, while authorities have tended to focus their development plans on the country’s vast middle and lower classes. Havens for elite money managers, it’s safe to say, haven’t traditionally been a priority for the ruling Communist Party.

Now, though, the concept isn’t so outlandish. The Chinese hedge fund industry is booming, thanks to cautious support from securities regulators and the gradual liberalization of local equity and bond markets. Assets under management have more than tripled over the past two years, while the total number of hedge funds almost doubled in 2016. Despite some scandals—including a high-profile market manipulation conviction—policymakers are starting to view hedge funds as worthwhile contributors to Asia’s largest economy.

For Yuhuang Shannan and at least 15 smaller fund towns scattered across the country, long-term success may ultimately depend on what kind of China emerges over the next few years. If President Xi Jinping’s government follows through on pledges to give markets and service industries a central role in the $11 trillion economy, the hedge fund boom has a lot further to run. If policymakers backtrack or the country proves pessimists right by tipping into a financial crisis, the air of tranquility in China’s Greenwich is unlikely to last.

In many ways, the evolution of Yuhuang Shannan mirrors that of the entire country. The area was used mostly for farmland until the 20th century, when industrialization brought factories and warehouses. About a decade ago the local government made a big push into services, promoting the area first as a tourism zone and then as a design hub. Neither of those efforts was successful, but when hedge funds began moving in and authorities heard about Greenwich, the idea for a fund managers’ village took root.

Security guards ride their scooters through the town.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Today, Yuhuang Shannan is one of the most prominent examples of what policymakers call “characteristic small towns.” The village hosts about 3,000 employees of funds and related businesses, a figure local officials predict will climb as new residential and office space comes online. Most managers commute to Yuhuang Shannan from nearby apartment buildings; Greenwich-style mansions are still rare in China. Yuhuang Shannan and other fund towns are designed to nurture up-and-coming businesses. “China is very government-driven,” says Mei Jianqun, director of Yuhuang Shannan’s town management committee. “It’s almost impossible to develop such a big industry without government-backed resources and the authorities’ leading role.”

For economic planners keen to reduce the nation’s reliance on infrastructure spending and heavy manufacturing, there’s a lot to like about hedge funds. They’re growing fast, creating high-skilled jobs, and adding more choice to a domestic investment landscape dominated by bubble-prone property and equity markets. Hedge funds fit into the country’s major development goals, said Zhu Congjiu, a vice governor of Zhejiang province, which includes Yuhuang Shannan and Hangzhou, in a speech in November.

Outside China, you’d be hard-pressed to find someone that optimistic about the industry’s prospects. Global hedge funds tracked by Hedge Fund Research suffered $70 billion of withdrawals last year as investors rebelled against high fees and lackluster returns. The investment pools posted an average gain of just 4.5 percent in 2016, trailing the S&P 500 by 5 percentage points, according to Eurekahedge.

New construction is underway near existing offices.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

While Chinese hedge funds lost money on average last year, they avoided a client backlash by outperforming local equity and credit markets. Funds tracked by Shanghai Suntime Information Technology were down 2.5 percent in 2016, vs. a 12 percent slide in the Shanghai Composite Index and a 10 percent retreat in high-yield corporate bonds. Client inflows fueled a 55 percent jump in industry assets, while the number of registered funds rose to a record 27,015, according to the Asset Management Association of China.

Charlie Wang, who ran Bank of America’s global equity quant group in London before leaving to start his own investment firm in 2015, launched two funds in China last year. He says the country’s markets have entered something of a sweet spot; while they’ve grown more sophisticated, adding new tools such as futures and options, they’re still inefficient enough to produce attractive returns for savvy managers. That’s thanks in part to the outsize impact of individual investors, who drive more than 80 percent of volume in the Chinese stock market, vs. about 15 percent in the U.S.

“It’s easier to achieve alpha here,” says Wang, 53, who oversees about 350 million yuan as the chairman of MD Grand Investments. He opened a commodity futures fund in Yuhuang Shannan last March and added an equity fund in July, connecting with some of his early clients through the village’s management committee.

To be sure, Chinese policymakers and hedge funds don’t always see eye to eye. When the nation’s stock market crashed in the summer of 2015, regulators blamed “vicious” short sellers for the selloff. They allowed hundreds of companies to suspend trading in their shares and all but killed the market for equity index futures, which was central to some of the nation’s most popular hedge fund strategies. Authorities also froze trading accounts, raided brokerages, and arrested Xu Xiang—known locally as “Hedge Fund Brother No. 1”—for market manipulation, a charge to which he later pleaded guilty.

The episode highlighted what could be the biggest risk to Chinese hedge funds over the long run: While the government says it embraces free markets, it’s still willing to go to extremes to assert control when times get tough. If, as many analysts expect, the country’s record corporate debt levels eventually lead to a market-roiling crisis, it’s anyone’s guess how authorities will react.

One of the town’s office building courtyards.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

For now, at least, policymakers appear to be rolling out the red carpet. Some government officials have even made the 7,000-mile pilgrimage to Greenwich—home to the likes of AQR Capital Management and Viking Global Investors—to learn what made the original hedge fund village such a big draw.

Bruce McGuire, who runs the Connecticut Hedge Fund Association, says he’s hosted four Chinese delegations in Greenwich over the past 12 months. The former Goldman Sachs Asset Management executive has also toured fund towns in Hangzhou and Beijing, and he predicts it won’t be long before the country develops its own global hedge fund powerhouses. When those firms eventually look for a base in the U.S., McGuire wants to make sure Greenwich is at the top of their list. “We’d like to get more than our fair share,” he says. “We want to attract the Bridgewater of China.”

Until then, Yuhuang Shannan Fund Town will serve as China’s launchpad. “When you’re still a small firm, even if you venture into Beijing or Shanghai, it’s hard to reach out to the right funding partners,” says Wang of MD Grand Investments. “It’s easier to talk with banks and brokerages as a member of a fund town. If you’re not in a center of funds, you’ll be ignored—the last thing you want as a startup.”

www.fotavgeia.blogspot.com

China's Hedge Fund Elite Live in Their Own Private Village

Hedge funds didn't exist in the world's second-largest economy five years ago. Now they have their own private village.

The Yuhuang Shannan Fund Town in Hangzhou, China.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Bloomberg News

Nestled between the Qiantang River and Jade Emperor Hill, the village of Yuhuang Shannan feels a world removed from the surrounding metropolis of Hangzhou. The city of 9 million is hectic and loud, while this gated community—on the same site where emperors in the Song dynasty prayed for good harvests centuries ago—is quiet and green, exuding the feeling of a laid-back, high-end oasis.

Like Greenwich, Conn., the leafy town an hour’s drive north of Wall Street, Yuhuang Shannan, about an hour from Shanghai by high-speed train, has become a big hit with the hedge fund crowd. So big, in fact, that local authorities turned the entire village—until recently a hub for the design industry—into an exclusive enclave for China’s aspiring masters of the universe.

These days, resident money managers and their guests are the only ones allowed past the guarded entrance to Yuhuang Shannan. Inside, villa-style office buildings offer rows of trading terminals and waterfront views. There’s a private elementary school partly staffed by non-Chinese teachers, a modern medical center, and a club for after-work schmoozing—all designed with discerning financiers in mind. Even local government officials are eager to please, standing ready to help the funds raise cash from state-run investors and navigate the bureaucracy.

In China, the total number of hedge funds almost doubled in 2016, and assets under management have more than tripled over the past two years

It’s no wonder more than 1,000 hedge funds and private equity funds, overseeing a combined 580 billion yuan ($84 billion), have registered in the village since its official rebranding in May 2015 as, straightforwardly enough, Yuhuang Shannan Fund Town. With subsidies amounting to 30 percent of a typical firm’s tax bill adding to the area’s appeal, Yuhuang Shannan now boasts one of China’s largest hedge fund clusters outside the megacities of Shanghai, Beijing, and Shenzhen.

Alumni of Goldman Sachs and Bank of America Merrill Lynch have moved in, while a representative of Connecticut-based Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund firm, is said to have made a recent visit. “The natural environment is fantastic, and I believe the cluster effect will become stronger and stronger,” says Ted Wang, a former co-head of equities trading for the Americas at Goldman Sachs who now runs Puissance Capital Management, a global investment firm with offices in New York and China. Wang has registered two of his Chinese equity funds in Yuhuang Shannan.

Not too long ago, the thought of a hedge fund village in Hangzhou, or anywhere else in China, would have struck most observers as absurd. Hedge funds weren’t officially recognized by Chinese lawmakers until 2012, while authorities have tended to focus their development plans on the country’s vast middle and lower classes. Havens for elite money managers, it’s safe to say, haven’t traditionally been a priority for the ruling Communist Party.

Now, though, the concept isn’t so outlandish. The Chinese hedge fund industry is booming, thanks to cautious support from securities regulators and the gradual liberalization of local equity and bond markets. Assets under management have more than tripled over the past two years, while the total number of hedge funds almost doubled in 2016. Despite some scandals—including a high-profile market manipulation conviction—policymakers are starting to view hedge funds as worthwhile contributors to Asia’s largest economy.

For Yuhuang Shannan and at least 15 smaller fund towns scattered across the country, long-term success may ultimately depend on what kind of China emerges over the next few years. If President Xi Jinping’s government follows through on pledges to give markets and service industries a central role in the $11 trillion economy, the hedge fund boom has a lot further to run. If policymakers backtrack or the country proves pessimists right by tipping into a financial crisis, the air of tranquility in China’s Greenwich is unlikely to last.

In many ways, the evolution of Yuhuang Shannan mirrors that of the entire country. The area was used mostly for farmland until the 20th century, when industrialization brought factories and warehouses. About a decade ago the local government made a big push into services, promoting the area first as a tourism zone and then as a design hub. Neither of those efforts was successful, but when hedge funds began moving in and authorities heard about Greenwich, the idea for a fund managers’ village took root.

Security guards ride their scooters through the town.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Today, Yuhuang Shannan is one of the most prominent examples of what policymakers call “characteristic small towns.” The village hosts about 3,000 employees of funds and related businesses, a figure local officials predict will climb as new residential and office space comes online. Most managers commute to Yuhuang Shannan from nearby apartment buildings; Greenwich-style mansions are still rare in China. Yuhuang Shannan and other fund towns are designed to nurture up-and-coming businesses. “China is very government-driven,” says Mei Jianqun, director of Yuhuang Shannan’s town management committee. “It’s almost impossible to develop such a big industry without government-backed resources and the authorities’ leading role.”

For economic planners keen to reduce the nation’s reliance on infrastructure spending and heavy manufacturing, there’s a lot to like about hedge funds. They’re growing fast, creating high-skilled jobs, and adding more choice to a domestic investment landscape dominated by bubble-prone property and equity markets. Hedge funds fit into the country’s major development goals, said Zhu Congjiu, a vice governor of Zhejiang province, which includes Yuhuang Shannan and Hangzhou, in a speech in November.

Outside China, you’d be hard-pressed to find someone that optimistic about the industry’s prospects. Global hedge funds tracked by Hedge Fund Research suffered $70 billion of withdrawals last year as investors rebelled against high fees and lackluster returns. The investment pools posted an average gain of just 4.5 percent in 2016, trailing the S&P 500 by 5 percentage points, according to Eurekahedge.

New construction is underway near existing offices.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

While Chinese hedge funds lost money on average last year, they avoided a client backlash by outperforming local equity and credit markets. Funds tracked by Shanghai Suntime Information Technology were down 2.5 percent in 2016, vs. a 12 percent slide in the Shanghai Composite Index and a 10 percent retreat in high-yield corporate bonds. Client inflows fueled a 55 percent jump in industry assets, while the number of registered funds rose to a record 27,015, according to the Asset Management Association of China.

Charlie Wang, who ran Bank of America’s global equity quant group in London before leaving to start his own investment firm in 2015, launched two funds in China last year. He says the country’s markets have entered something of a sweet spot; while they’ve grown more sophisticated, adding new tools such as futures and options, they’re still inefficient enough to produce attractive returns for savvy managers. That’s thanks in part to the outsize impact of individual investors, who drive more than 80 percent of volume in the Chinese stock market, vs. about 15 percent in the U.S.

“It’s easier to achieve alpha here,” says Wang, 53, who oversees about 350 million yuan as the chairman of MD Grand Investments. He opened a commodity futures fund in Yuhuang Shannan last March and added an equity fund in July, connecting with some of his early clients through the village’s management committee.

To be sure, Chinese policymakers and hedge funds don’t always see eye to eye. When the nation’s stock market crashed in the summer of 2015, regulators blamed “vicious” short sellers for the selloff. They allowed hundreds of companies to suspend trading in their shares and all but killed the market for equity index futures, which was central to some of the nation’s most popular hedge fund strategies. Authorities also froze trading accounts, raided brokerages, and arrested Xu Xiang—known locally as “Hedge Fund Brother No. 1”—for market manipulation, a charge to which he later pleaded guilty.

The episode highlighted what could be the biggest risk to Chinese hedge funds over the long run: While the government says it embraces free markets, it’s still willing to go to extremes to assert control when times get tough. If, as many analysts expect, the country’s record corporate debt levels eventually lead to a market-roiling crisis, it’s anyone’s guess how authorities will react.

One of the town’s office building courtyards.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

For now, at least, policymakers appear to be rolling out the red carpet. Some government officials have even made the 7,000-mile pilgrimage to Greenwich—home to the likes of AQR Capital Management and Viking Global Investors—to learn what made the original hedge fund village such a big draw.

Bruce McGuire, who runs the Connecticut Hedge Fund Association, says he’s hosted four Chinese delegations in Greenwich over the past 12 months. The former Goldman Sachs Asset Management executive has also toured fund towns in Hangzhou and Beijing, and he predicts it won’t be long before the country develops its own global hedge fund powerhouses. When those firms eventually look for a base in the U.S., McGuire wants to make sure Greenwich is at the top of their list. “We’d like to get more than our fair share,” he says. “We want to attract the Bridgewater of China.”

Until then, Yuhuang Shannan Fund Town will serve as China’s launchpad. “When you’re still a small firm, even if you venture into Beijing or Shanghai, it’s hard to reach out to the right funding partners,” says Wang of MD Grand Investments. “It’s easier to talk with banks and brokerages as a member of a fund town. If you’re not in a center of funds, you’ll be ignored—the last thing you want as a startup.”

www.fotavgeia.blogspot.com

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου