Αrt3159 Μ.Τετάρτη 12 Απριλίου 2017

The Most American City Isn’t New York, L.A., Or Chicago

Long dismissed, this one city’s design gets the credit it’s due in a new book from MIT Press.

BY STEFAN AL

Editors’ Note: In The Strip, a new book from MIT Press, Stefan Al–an architect, urban designer, and associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania–compares the evolution of Las Vegas to the cultural metamorphosis of the American dream. The following chapter is excerpted, with permission.The Strip began as an exception. But increasingly it has become a rule—in its holistically designed and multisensory environments, in being technologically wired and “smart,” in patterns of urban development, in financial practices, and in aesthetic tastes. For decades, Vegas marketed itself as an over-the-top series of urban stunts. But this seemingly outrageous behavior took advantage of fundamental changes in American society. The urbanistic role of Vegas has also taken a turn. The Strip began as essentially anti-urban, with inwardly oriented resorts located outside of the incorporated city of Las Vegas. Today, the Strip is a major pedestrian space with casinos that contribute to a larger urban experience. Vegas has now even become a model for 21st-century urbanism that other cities are seeking to emulate. Not only that, the city provides lessons for anyone called upon to create landmarks, attention-getters, fantasy environments, spectacular images, or memorable experiences. I personally witnessed the city’s impact as an architect when Chinese clients for the world’s largest tower, after a visit to the Strip, wanted the Bellagio’s musical fountains. They wanted Vegas.

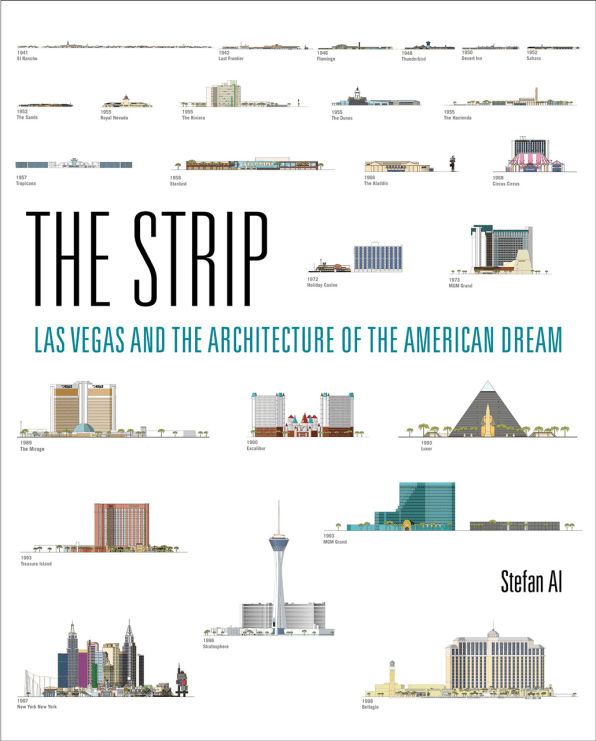

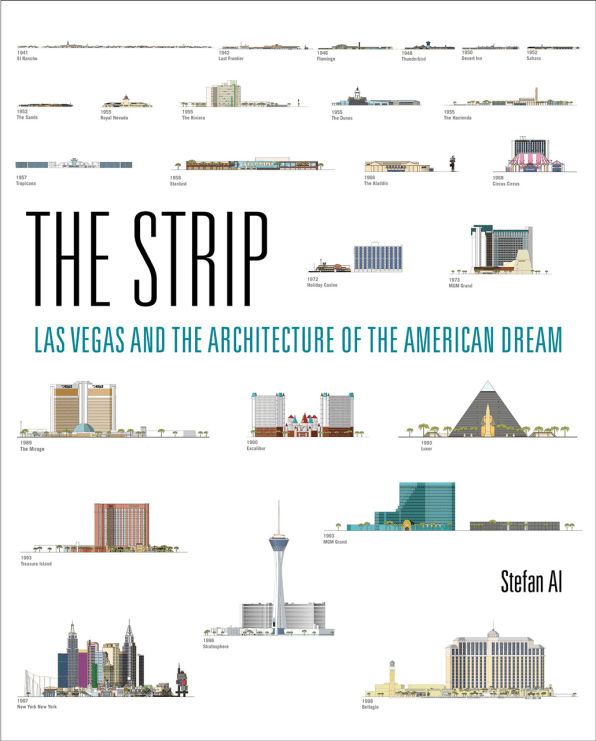

[Image: courtesy MIT Press]From its inception in 1941, the Strip has mutated beyond even its own wildest dreams. In the 1940s, Strip developers dressed like cowboys, some packing real guns, built hacienda-style casinos that broke ground with moving neon displays as big as windmills. By the 1950s, casino builders replaced the wagon wheels with Cadillac tailfin forms, and pumped underwater Muzak into exotically shaped pools. The 1960s neon signs, as tall as 20-story buildings and as long as two football fields, were ripped down in the 1970s when the emphasis shifted to the buildings themselves, and chandeliers the size of trucks. By the next decade, the chandeliers had been replaced by a 10-story, laser-eyed sphinx and a fiery volcano spewing piña colada scent. Charmed by the world’s famous cities in the late 1990s, Las Vegas built replicas, including the Eiffel Tower, New York skyscrapers, and Venetian canals. But in the new millennium, a mere decade later, replicas were out and serious architectural originals, which housed museum-quality collections of authentic art, were in.

[Image: courtesy MIT Press]From its inception in 1941, the Strip has mutated beyond even its own wildest dreams. In the 1940s, Strip developers dressed like cowboys, some packing real guns, built hacienda-style casinos that broke ground with moving neon displays as big as windmills. By the 1950s, casino builders replaced the wagon wheels with Cadillac tailfin forms, and pumped underwater Muzak into exotically shaped pools. The 1960s neon signs, as tall as 20-story buildings and as long as two football fields, were ripped down in the 1970s when the emphasis shifted to the buildings themselves, and chandeliers the size of trucks. By the next decade, the chandeliers had been replaced by a 10-story, laser-eyed sphinx and a fiery volcano spewing piña colada scent. Charmed by the world’s famous cities in the late 1990s, Las Vegas built replicas, including the Eiffel Tower, New York skyscrapers, and Venetian canals. But in the new millennium, a mere decade later, replicas were out and serious architectural originals, which housed museum-quality collections of authentic art, were in.

If any city deserves the “Makeover Award” for the most drastic changes to its image, it is Las Vegas.

[Photo: courtesy MIT Press]But as outrageous as the Strip’s excesses may seem, it has always been the ultimate manifestation of a quintessentially American practice: marketing. At the peak of the popularity of western movies, casino builders welcomed guests with cowboy saloons featuring stuffed buffalo heads. On the cusp of the suburbanization of America, they built bungalows with lavish pools and verdant lawns. When the space age and nuclear testing enthralled the nation, they enveloped guests with neon planets and plastered a casino with a sign of the atom bomb. Even before Gordon Gekko celebrated unfettered materialism in the movie Wall Street, developers built mirror-clad, corporate modernist casinos. When Disney became the world’s number one entertainment corporation, Vegas casinos built entire theme parks and a larger-than-life Cinderella castle. As heritage tourism flourished, and Americans became fascinated with design from former eras, developers reciprocated by enhancing their casinos with belle époque monuments. And when other cities built architectural icons to attract tourists, Las Vegas developers commissioned the world’s “Starchitects.” The history of the Strip represents the ever-evolving architecture of the American dream.

[Photo: courtesy MIT Press]But as outrageous as the Strip’s excesses may seem, it has always been the ultimate manifestation of a quintessentially American practice: marketing. At the peak of the popularity of western movies, casino builders welcomed guests with cowboy saloons featuring stuffed buffalo heads. On the cusp of the suburbanization of America, they built bungalows with lavish pools and verdant lawns. When the space age and nuclear testing enthralled the nation, they enveloped guests with neon planets and plastered a casino with a sign of the atom bomb. Even before Gordon Gekko celebrated unfettered materialism in the movie Wall Street, developers built mirror-clad, corporate modernist casinos. When Disney became the world’s number one entertainment corporation, Vegas casinos built entire theme parks and a larger-than-life Cinderella castle. As heritage tourism flourished, and Americans became fascinated with design from former eras, developers reciprocated by enhancing their casinos with belle époque monuments. And when other cities built architectural icons to attract tourists, Las Vegas developers commissioned the world’s “Starchitects.” The history of the Strip represents the ever-evolving architecture of the American dream.

Over a period of 70 years, developers have built a more sophisticated “Mousetrap.” The casino has come a long way from the original small box with about 50 rooms to thousand-room megastructures, the earth’s largest. The Strip’s first casinos were low-rise bungalows surrounded by surface parking; the latest incarnations are high-rise towers with underground parking. The first casinos followed the “island” model resort, isolating guests with buildings set back from the Strip, but they now abide by the urban model, fully enmeshed into the sidewalk. Initially the only entertainment was a lounge act; today there are entire arenas, Broadway theaters, and the world’s largest nightclubs. At first the revenue came from the gambling hall; now the casino complex generates more from conventions, nightlife, restaurants, and retail. Once known for their five-dollar steaks and cheap motels, casinos presently lure guests with celebrity chefs and luxury suites.

There have been times when Las Vegas was considered tacky—and it still is by some. But today the Strip is becoming an authority on art, performance, and architecture, with multimillion-dollar art collections, a lineup of Cirque du Soleil shows, and buildings designed by star architects. Moreover, the Bellagio, a Las Vegas casino, is the most popular recent building in America, according to America’s Favorite Architecture, a poll by the American Institute of Architects. Meanwhile, as public budgets for museums and shared spaces decline, while art collections and streets are being privatized, the Strip is reflective of a world in which the lines between private and public are increasingly blurred. While the distinction between mass consumerism and elite culture continues to fade, with museums run more and more like franchises, Las Vegas already perfected the art of “exit through the gift shop.”

[Photo: courtesy MIT Press]The fact that the Strip keeps updating itself to the latest fad in architecture obviously leads to destruction and waste; on the other hand, it has created publicly accessible architectural marvels that attract many to the desert. On the positive side of the Strip’s “creative destruction” lay the most holistically and sensually created environments, and unbridled place-making freed from traditional ideas.

[Photo: courtesy MIT Press]The fact that the Strip keeps updating itself to the latest fad in architecture obviously leads to destruction and waste; on the other hand, it has created publicly accessible architectural marvels that attract many to the desert. On the positive side of the Strip’s “creative destruction” lay the most holistically and sensually created environments, and unbridled place-making freed from traditional ideas.

To everyone’s surprise, despite more relaxed planning regulations, the Las Vegas Strip has become one of the most pedestrian-oriented urban areas in the American West. The great irony was that corporatism, rather than planning theory, caused this shift. As the Strip became denser, as a result of its success, corporations implemented urban design principles to appeal to pedestrians as well as automobilists. Instead of blank concrete walls and asphalt parking lots, they built “active” streets with restaurants, fronted them with pocket parks and landscaped sidewalks, and even arranged terraces and benches. If the postwar Strip was symptomatic of the suburban sprawl of the United States, the 21st-century Strip is representative of a nationwide migration from suburbia back to the cities, America’s “urban renaissance.”

America changed along with Las Vegas.

The Strip adapted to changing trends with such overwhelming financial success that it has even become a global model for urban development. Singapore, despite its moral objections to gambling, has built its new central business district around a Las Vegas-styled casino. Macau has reclaimed hundreds of acres of the South China Sea, only to build a Las Vegas-style Strip. Ironically, with casinos thriving in these and other places, Las Vegas may be eclipsed by the very model it helped create.

Vegas operators are so finely tuned to pleasing their guests that the Strip is a pioneer in the “experience economy,” in which companies compete for customers by staging memorable experiences. As creepy as it may be, casinos track their guests, knowing where they have been, or whether they drank coffee or tea. Vegas tracking technology is so advanced that after 9/11, Homeland Security visited Las Vegas to learn about surveillance. As wasteful it may be to have megastructures in the desert, the city now leads the world in water-saving techniques, with casinos even developing their own low-flow showerheads.

Where gambling in the United States used to be contained in the remote Mojave Desert—for the same reason it was a site for nuclear detonations—today hundreds of casinos have entered Indian reservations and American cities. Following the Strip’s privately managed sidewalks and plazas that lure tourists to try their luck, public space in other cities has also become increasingly privatized, converting citizens into consumers, one by one. These days, Mob king “Bugsy” Siegel’s “build it and they will come” attitude finds its equivalent in cities’ desperate attempts to build icons that attract tourists. In a world where every metropolis is a competitor for visitors, cities learn from Las Vegas’s continuous reinvention to “fix” their own image. The Strip-style economy, shaken up by high risk-taking and the whims of individuals like casino mogul Sheldon Adelson, has become the formula for “casino capitalism” worldwide. Built in the middle of the Mojave Desert, Las Vegas has faced a water crisis since its founding, while other cities now face environmental hazards such as floods and droughts resulting from manmade climate change.

When the first casino developers hung cow horns on walls and guns on their hips, critics derided Las Vegas as fake. But billions of dollars of investments and hundreds of thousands of jobs over a century are no desert mirage. Ever since the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations built the Boulder Dam, the political economy of Las Vegas’s development has reflected America as a whole. While Lake Mead still provides the water and the hydroelectric force to power the Strip’s bright lights, today American ideology has shifted toward deregulation and neoliberal prioritization of private enterprise, with Las Vegas as the avatar once again. Las Vegas, however, has been more than a mirror of society alone. The city shaped both American and global urbanization, setting a template for practices of city branding, spatial production, and control, and high-risk investment in urban spaces. The Strip is both a promoter of hypercapitalism and a paragon of modernity in which “all that is solid melts into air.”

In its current incarnation, the Strip continues to lead the charge in innovation and setting the tone. Our cities are affected by an increasing number of casinos, the tourist industry, rampant consumerism, fickle casino capitalism, and environmental crises. That once dusty, potholed road stretching through a barren desert wasteland has grown into one of the world’s most visited boulevards, with an impact that is felt worldwide. Today, we all live in Las Vegas.

Excerpted from The Strip by Stefan Al, published this month by MIT Press copyright 2017 MIT Press. All rights reserved.Α

www.fotavgeia.blogspot.com

The Most American City Isn’t New York, L.A., Or Chicago

Long dismissed, this one city’s design gets the credit it’s due in a new book from MIT Press.

BY STEFAN AL

Editors’ Note: In The Strip, a new book from MIT Press, Stefan Al–an architect, urban designer, and associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania–compares the evolution of Las Vegas to the cultural metamorphosis of the American dream. The following chapter is excerpted, with permission.The Strip began as an exception. But increasingly it has become a rule—in its holistically designed and multisensory environments, in being technologically wired and “smart,” in patterns of urban development, in financial practices, and in aesthetic tastes. For decades, Vegas marketed itself as an over-the-top series of urban stunts. But this seemingly outrageous behavior took advantage of fundamental changes in American society. The urbanistic role of Vegas has also taken a turn. The Strip began as essentially anti-urban, with inwardly oriented resorts located outside of the incorporated city of Las Vegas. Today, the Strip is a major pedestrian space with casinos that contribute to a larger urban experience. Vegas has now even become a model for 21st-century urbanism that other cities are seeking to emulate. Not only that, the city provides lessons for anyone called upon to create landmarks, attention-getters, fantasy environments, spectacular images, or memorable experiences. I personally witnessed the city’s impact as an architect when Chinese clients for the world’s largest tower, after a visit to the Strip, wanted the Bellagio’s musical fountains. They wanted Vegas.

[Image: courtesy MIT Press]From its inception in 1941, the Strip has mutated beyond even its own wildest dreams. In the 1940s, Strip developers dressed like cowboys, some packing real guns, built hacienda-style casinos that broke ground with moving neon displays as big as windmills. By the 1950s, casino builders replaced the wagon wheels with Cadillac tailfin forms, and pumped underwater Muzak into exotically shaped pools. The 1960s neon signs, as tall as 20-story buildings and as long as two football fields, were ripped down in the 1970s when the emphasis shifted to the buildings themselves, and chandeliers the size of trucks. By the next decade, the chandeliers had been replaced by a 10-story, laser-eyed sphinx and a fiery volcano spewing piña colada scent. Charmed by the world’s famous cities in the late 1990s, Las Vegas built replicas, including the Eiffel Tower, New York skyscrapers, and Venetian canals. But in the new millennium, a mere decade later, replicas were out and serious architectural originals, which housed museum-quality collections of authentic art, were in.

[Image: courtesy MIT Press]From its inception in 1941, the Strip has mutated beyond even its own wildest dreams. In the 1940s, Strip developers dressed like cowboys, some packing real guns, built hacienda-style casinos that broke ground with moving neon displays as big as windmills. By the 1950s, casino builders replaced the wagon wheels with Cadillac tailfin forms, and pumped underwater Muzak into exotically shaped pools. The 1960s neon signs, as tall as 20-story buildings and as long as two football fields, were ripped down in the 1970s when the emphasis shifted to the buildings themselves, and chandeliers the size of trucks. By the next decade, the chandeliers had been replaced by a 10-story, laser-eyed sphinx and a fiery volcano spewing piña colada scent. Charmed by the world’s famous cities in the late 1990s, Las Vegas built replicas, including the Eiffel Tower, New York skyscrapers, and Venetian canals. But in the new millennium, a mere decade later, replicas were out and serious architectural originals, which housed museum-quality collections of authentic art, were in.If any city deserves the “Makeover Award” for the most drastic changes to its image, it is Las Vegas.

[Photo: courtesy MIT Press]But as outrageous as the Strip’s excesses may seem, it has always been the ultimate manifestation of a quintessentially American practice: marketing. At the peak of the popularity of western movies, casino builders welcomed guests with cowboy saloons featuring stuffed buffalo heads. On the cusp of the suburbanization of America, they built bungalows with lavish pools and verdant lawns. When the space age and nuclear testing enthralled the nation, they enveloped guests with neon planets and plastered a casino with a sign of the atom bomb. Even before Gordon Gekko celebrated unfettered materialism in the movie Wall Street, developers built mirror-clad, corporate modernist casinos. When Disney became the world’s number one entertainment corporation, Vegas casinos built entire theme parks and a larger-than-life Cinderella castle. As heritage tourism flourished, and Americans became fascinated with design from former eras, developers reciprocated by enhancing their casinos with belle époque monuments. And when other cities built architectural icons to attract tourists, Las Vegas developers commissioned the world’s “Starchitects.” The history of the Strip represents the ever-evolving architecture of the American dream.

[Photo: courtesy MIT Press]But as outrageous as the Strip’s excesses may seem, it has always been the ultimate manifestation of a quintessentially American practice: marketing. At the peak of the popularity of western movies, casino builders welcomed guests with cowboy saloons featuring stuffed buffalo heads. On the cusp of the suburbanization of America, they built bungalows with lavish pools and verdant lawns. When the space age and nuclear testing enthralled the nation, they enveloped guests with neon planets and plastered a casino with a sign of the atom bomb. Even before Gordon Gekko celebrated unfettered materialism in the movie Wall Street, developers built mirror-clad, corporate modernist casinos. When Disney became the world’s number one entertainment corporation, Vegas casinos built entire theme parks and a larger-than-life Cinderella castle. As heritage tourism flourished, and Americans became fascinated with design from former eras, developers reciprocated by enhancing their casinos with belle époque monuments. And when other cities built architectural icons to attract tourists, Las Vegas developers commissioned the world’s “Starchitects.” The history of the Strip represents the ever-evolving architecture of the American dream.Over a period of 70 years, developers have built a more sophisticated “Mousetrap.” The casino has come a long way from the original small box with about 50 rooms to thousand-room megastructures, the earth’s largest. The Strip’s first casinos were low-rise bungalows surrounded by surface parking; the latest incarnations are high-rise towers with underground parking. The first casinos followed the “island” model resort, isolating guests with buildings set back from the Strip, but they now abide by the urban model, fully enmeshed into the sidewalk. Initially the only entertainment was a lounge act; today there are entire arenas, Broadway theaters, and the world’s largest nightclubs. At first the revenue came from the gambling hall; now the casino complex generates more from conventions, nightlife, restaurants, and retail. Once known for their five-dollar steaks and cheap motels, casinos presently lure guests with celebrity chefs and luxury suites.

There have been times when Las Vegas was considered tacky—and it still is by some. But today the Strip is becoming an authority on art, performance, and architecture, with multimillion-dollar art collections, a lineup of Cirque du Soleil shows, and buildings designed by star architects. Moreover, the Bellagio, a Las Vegas casino, is the most popular recent building in America, according to America’s Favorite Architecture, a poll by the American Institute of Architects. Meanwhile, as public budgets for museums and shared spaces decline, while art collections and streets are being privatized, the Strip is reflective of a world in which the lines between private and public are increasingly blurred. While the distinction between mass consumerism and elite culture continues to fade, with museums run more and more like franchises, Las Vegas already perfected the art of “exit through the gift shop.”

[Photo: courtesy MIT Press]The fact that the Strip keeps updating itself to the latest fad in architecture obviously leads to destruction and waste; on the other hand, it has created publicly accessible architectural marvels that attract many to the desert. On the positive side of the Strip’s “creative destruction” lay the most holistically and sensually created environments, and unbridled place-making freed from traditional ideas.

[Photo: courtesy MIT Press]The fact that the Strip keeps updating itself to the latest fad in architecture obviously leads to destruction and waste; on the other hand, it has created publicly accessible architectural marvels that attract many to the desert. On the positive side of the Strip’s “creative destruction” lay the most holistically and sensually created environments, and unbridled place-making freed from traditional ideas.To everyone’s surprise, despite more relaxed planning regulations, the Las Vegas Strip has become one of the most pedestrian-oriented urban areas in the American West. The great irony was that corporatism, rather than planning theory, caused this shift. As the Strip became denser, as a result of its success, corporations implemented urban design principles to appeal to pedestrians as well as automobilists. Instead of blank concrete walls and asphalt parking lots, they built “active” streets with restaurants, fronted them with pocket parks and landscaped sidewalks, and even arranged terraces and benches. If the postwar Strip was symptomatic of the suburban sprawl of the United States, the 21st-century Strip is representative of a nationwide migration from suburbia back to the cities, America’s “urban renaissance.”

America changed along with Las Vegas.

The Strip adapted to changing trends with such overwhelming financial success that it has even become a global model for urban development. Singapore, despite its moral objections to gambling, has built its new central business district around a Las Vegas-styled casino. Macau has reclaimed hundreds of acres of the South China Sea, only to build a Las Vegas-style Strip. Ironically, with casinos thriving in these and other places, Las Vegas may be eclipsed by the very model it helped create.

Vegas operators are so finely tuned to pleasing their guests that the Strip is a pioneer in the “experience economy,” in which companies compete for customers by staging memorable experiences. As creepy as it may be, casinos track their guests, knowing where they have been, or whether they drank coffee or tea. Vegas tracking technology is so advanced that after 9/11, Homeland Security visited Las Vegas to learn about surveillance. As wasteful it may be to have megastructures in the desert, the city now leads the world in water-saving techniques, with casinos even developing their own low-flow showerheads.

Where gambling in the United States used to be contained in the remote Mojave Desert—for the same reason it was a site for nuclear detonations—today hundreds of casinos have entered Indian reservations and American cities. Following the Strip’s privately managed sidewalks and plazas that lure tourists to try their luck, public space in other cities has also become increasingly privatized, converting citizens into consumers, one by one. These days, Mob king “Bugsy” Siegel’s “build it and they will come” attitude finds its equivalent in cities’ desperate attempts to build icons that attract tourists. In a world where every metropolis is a competitor for visitors, cities learn from Las Vegas’s continuous reinvention to “fix” their own image. The Strip-style economy, shaken up by high risk-taking and the whims of individuals like casino mogul Sheldon Adelson, has become the formula for “casino capitalism” worldwide. Built in the middle of the Mojave Desert, Las Vegas has faced a water crisis since its founding, while other cities now face environmental hazards such as floods and droughts resulting from manmade climate change.

When the first casino developers hung cow horns on walls and guns on their hips, critics derided Las Vegas as fake. But billions of dollars of investments and hundreds of thousands of jobs over a century are no desert mirage. Ever since the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations built the Boulder Dam, the political economy of Las Vegas’s development has reflected America as a whole. While Lake Mead still provides the water and the hydroelectric force to power the Strip’s bright lights, today American ideology has shifted toward deregulation and neoliberal prioritization of private enterprise, with Las Vegas as the avatar once again. Las Vegas, however, has been more than a mirror of society alone. The city shaped both American and global urbanization, setting a template for practices of city branding, spatial production, and control, and high-risk investment in urban spaces. The Strip is both a promoter of hypercapitalism and a paragon of modernity in which “all that is solid melts into air.”

In its current incarnation, the Strip continues to lead the charge in innovation and setting the tone. Our cities are affected by an increasing number of casinos, the tourist industry, rampant consumerism, fickle casino capitalism, and environmental crises. That once dusty, potholed road stretching through a barren desert wasteland has grown into one of the world’s most visited boulevards, with an impact that is felt worldwide. Today, we all live in Las Vegas.

Excerpted from The Strip by Stefan Al, published this month by MIT Press copyright 2017 MIT Press. All rights reserved.Α

www.fotavgeia.blogspot.com

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου